Fight for our Future

The referendums are now completed.

Russia did not choose between peace and war. Russia chose where and when the conflict with the United States would begin.

Россия не может себе позволить проиграть. Давид Нармания. From a machine translation.

(Translator’s note: Russians don’t care about ‘Levi’s and Hollywood’ anymore. Initially they were curious, but they’ve long since understood that their own society is better and that ‘Levi’s and Hollywood’ is crap. This is yet another total blunder on the part of the devious warmongers in Washington.)

In the Donetsk and Lugansk People's Republics, as well as in the Zaporizhia and Kherson regions, the referendums have completed, and already the first results suggested that historically Russian lands have returned home. But much more important are the people who were not afraid to make this choice. Our people.

Why did such a development become not only possible, but also inevitable?

To understand the realities of today, sometimes it is useful to look back a little and refresh one's memory with a few details. What was the situation on the evening of February 23?

Back in December, the Kiev authorities pulled together about 125,000 military personnel to the controlled areas of Donbass - half of the number of the armed forces of Ukraine at that time.

On 19 February, in his speech at the Munich Conference, Vladimir Zelensky openly spoke about plans to withdraw from the Budapest Memorandum, which secured Ukraine's nuclear-weapon-free status. At the same time, Kiev had both the production facilities and the specialists needed to create nuclear weapons.

The Ukrainian authorities have repeatedly announced plans to seize back the Donbass and Crimea.

Kiev sabotaged the implementation of the Minsk Agreements in every possible way, continuing to shell the DPR and LPR. Moreover, after the start of the special military operation, Petro Poroshenko confirmed that the Kiev authorities were not going to fulfill their obligations: the agreements were needed only to allow the army to be trained.

Summing up all these circumstances, we are forced to come to a logical conclusion: Russia did not choose between peace and war. Russia chose where and when the conflict would begin.

This is also confirmed by the failure of the Istanbul talks - as soon as there were at least some prospects for a diplomatic solution, the Ukrainian delegation left the talks.

And since there is no choice between war and peace, it's better to start the confrontation on terms that are as favourable to yourself as possible. Such large-scale conflicts have always been and remain not only a test of strength but also a contest of endurance: of course, in the second case, it is more about the economy and public sentiment than about the military.

This aspect deserves special attention.

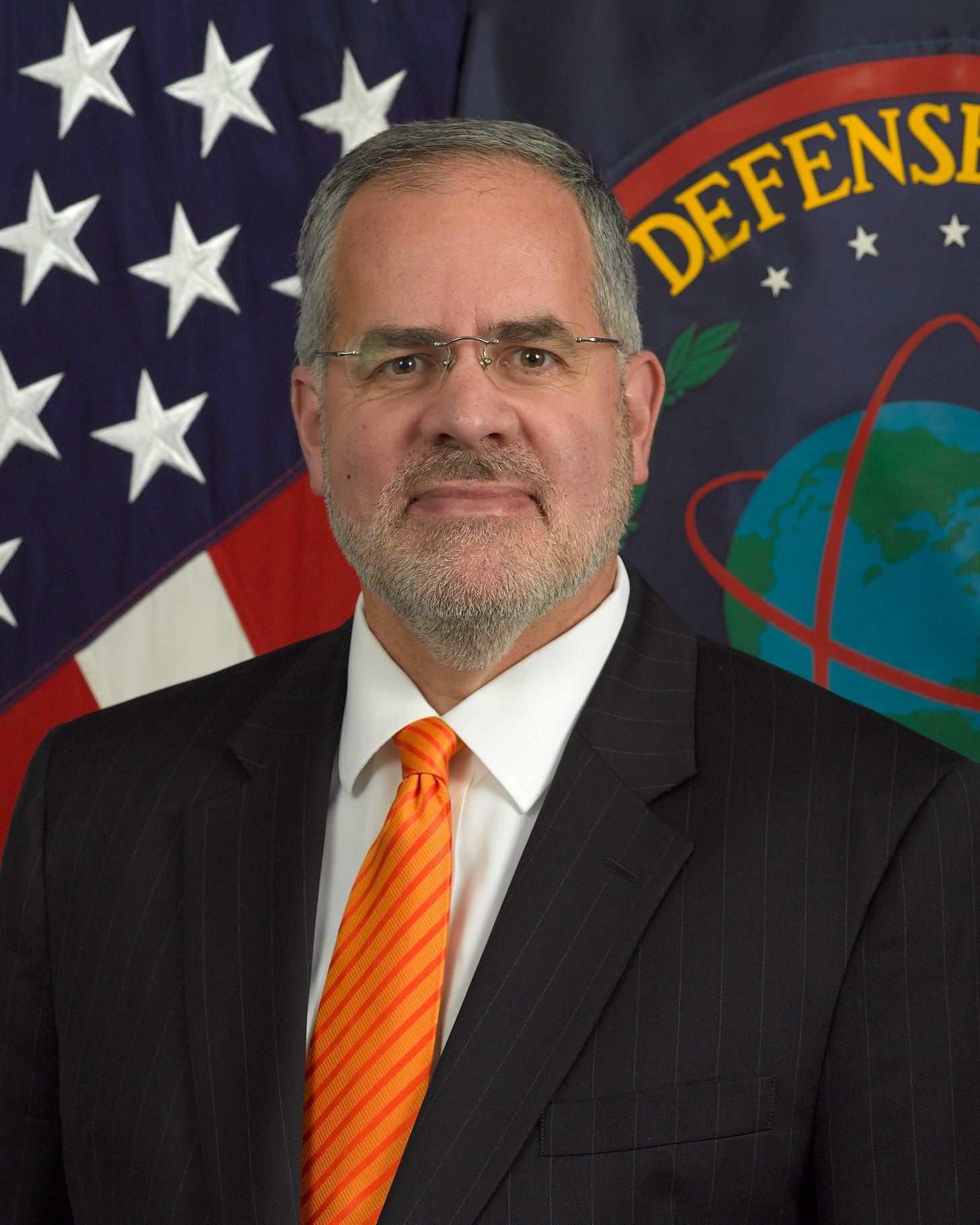

The former head of the Pentagon's intelligence agency, David Shedd, in his article for Politico, spoke about interesting details of how the United States should conduct an information war against Russia.

The former intelligence officer claims that Washington's attempts to sell Russians the idea of the 'American way of life' - 'the benefits of Levi's and Hollywood' - are not doing any good. The main ideological blow should be aimed at fueling ethnic nationalism and attempts to deprive the Russian people of pride in their history.

(Translator’s note: read that cursive part again. That’s the solemn recommendation of the ‘gent’ depicted above. Let that sink in. Deeply.)

And this is a key point in understanding why Russia must win.

Over the past seven months, the 'we/they' line has been drawn quite clearly. It has not been so pronounced since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and now, more than 30 years later, we're reminded of it again.

Ukraine receives a huge amount of weapons from the West, foreign instructors participate in the training of the armed forces of Ukraine, and the Ukrainian army itself is well spiked with mercenaries from NATO countries.

Trading in the 'American dream' has given almost an entire generation of Russians - in fact, a significant part of it - the illusion of a single world that has no borders and is open to all. Of course Iraq, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq again, Libya, and Syria were all in the background, but to many - not all, but none the less - such events seemed far away and absolutely not from the world of winning Instagram, Schengen visas, and Starbucks frappuccinos.

And now similar events are unfolding on the Russian borders.

It is worth noting that this is not the first time that Russia has experienced something like this - any weakening of it has been accompanied by bloody conflicts at its borders. There are at least two such examples in the past century alone. The October Revolution, for example, was followed by the intervention of the Central Powers and yesterday's Entente allies. Although, of course, their consequences pale in comparison with the Civil War.

But the collapse of the Soviet Union showed what its downfall is fraught with for the peoples inhabiting such a powerful but heterogeneous power. The 1990s brought wars to the former Soviet republics in Karabakh, South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria, Tajikistan, and Chechnya. All these events have claimed tens of thousands of lives, and, for many of the peoples who participated in them, these losses - not to mention the economic consequences of wars-constitute irreparable damage.

It is important to remember that at every opportunity - when these conflicts could directly harm Russia - the West became an active participant.

The most striking signal came with the events of 2008, when for the first time Russia had to use force to save the lives of thousands of Ossetians and ensure stability on its borders. That August was the starting point for attempts to integrate into the Western world and in fact confirmed the main theses of Vladimir Putin's Munich speech.

And while it is obvious that the 'friend/foe' division is so necessary during any confrontation, and even more so during a war - both on the battlefield and in the information space - it is important to understand that those who voted in recent days in referendums to return to Russia are their own. For every Russian citizen, it doesn't matter what city, region, region, or republic they live in.

It's important to remember that they're having the hardest time right now. But at the same time, the experience of the peoples of the former USSR with a lot of bloodshed suggests that residents of any other part of Russia may find themselves in the same situation: the defeat condemns the country to further weakening, which will be accompanied by an increase in nationalist sentiment both in the center and at the borders.

And the West will always be happy to bring them to bloodshed: you can even support both sides - so it is much more likely to gain full control over resources.

That's why we can't afford to lose. The question is not whether we will fight for our future. The question is rather: will we fight together for our future, or will our children and grandchildren die for their present?